Since 2000, the house has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

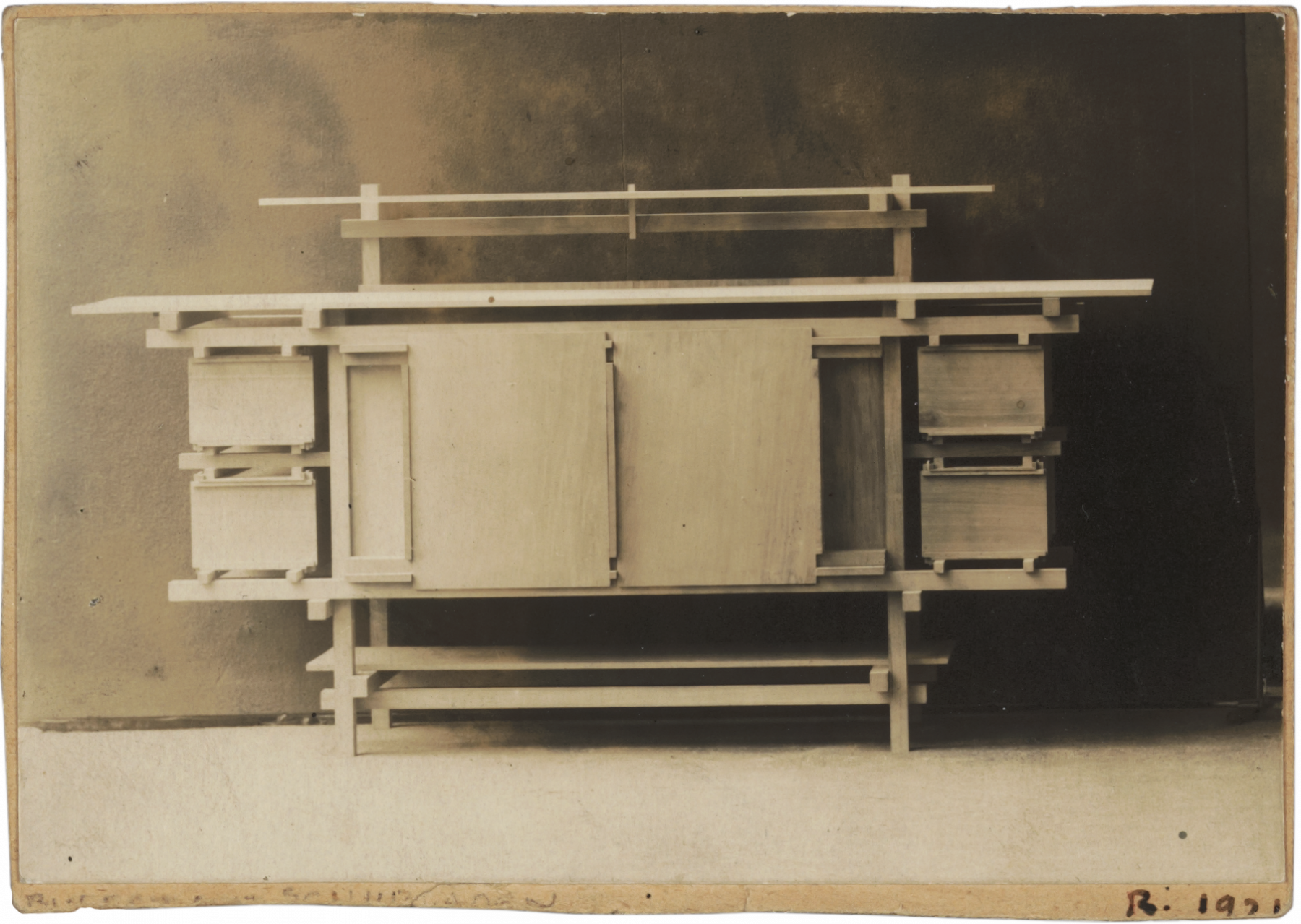

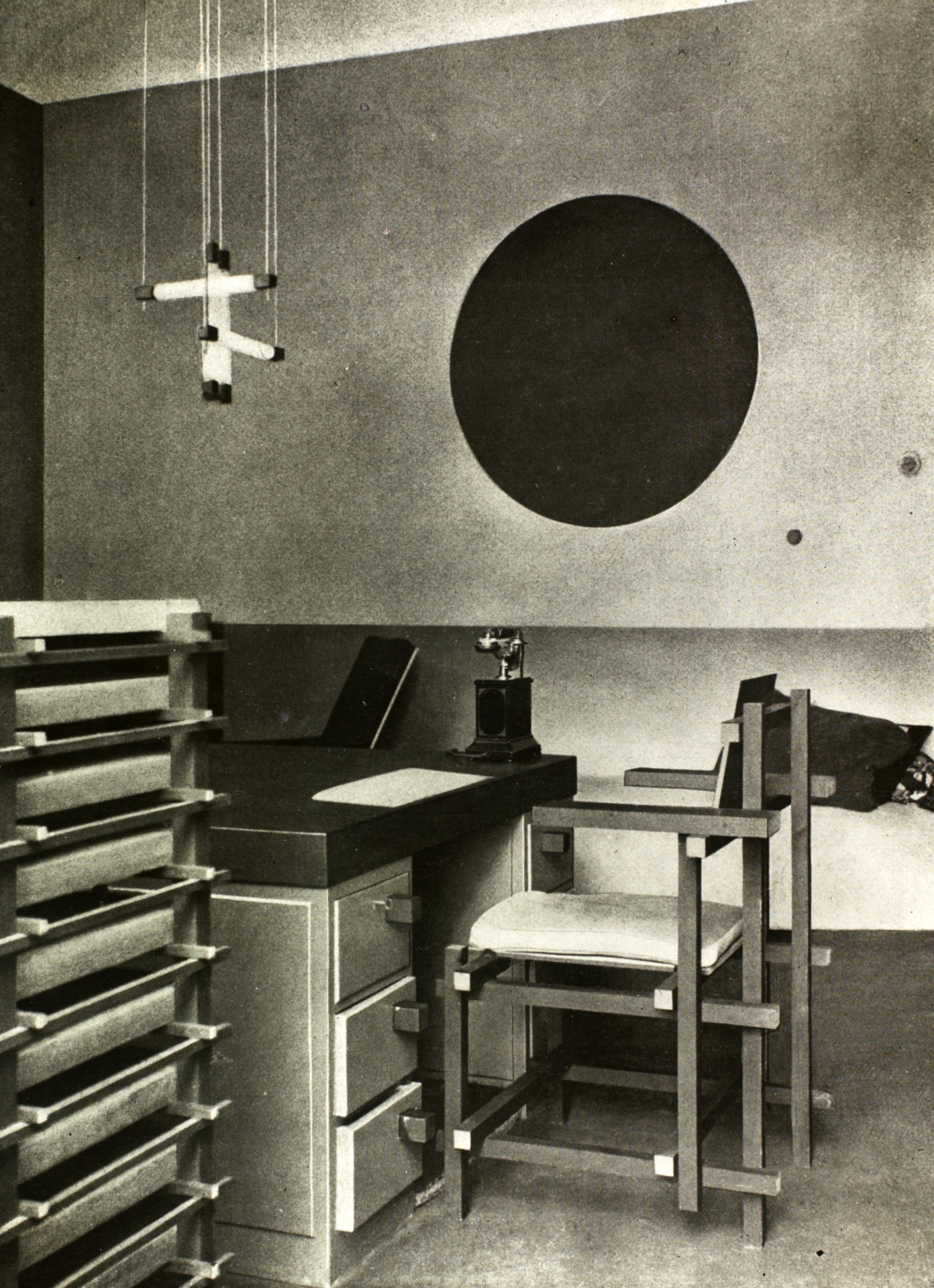

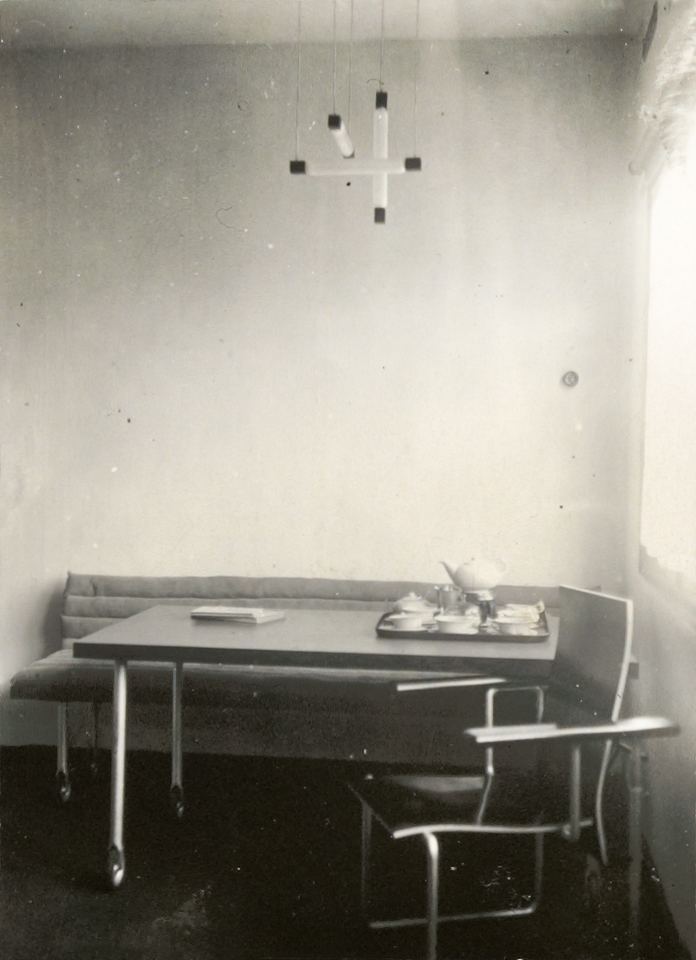

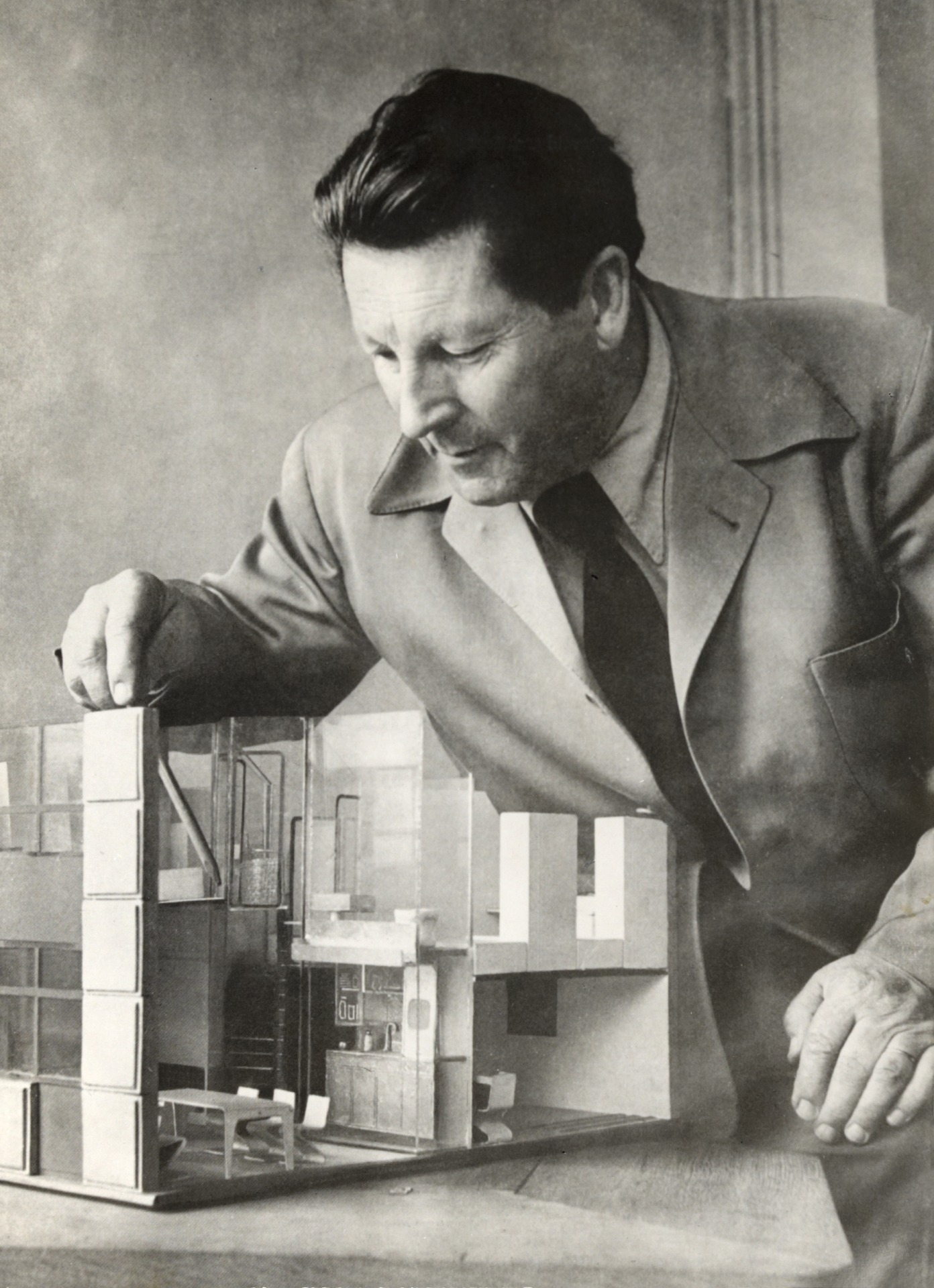

Throughout his life, Rietveld continued to make “small things”, as he called them: furniture, chairs, serving as spatial constructions to solve all kinds of issues, which he could put to good use again in architecture. Initially this was out of necessity, because he received very few commissions. He mentioned about this:

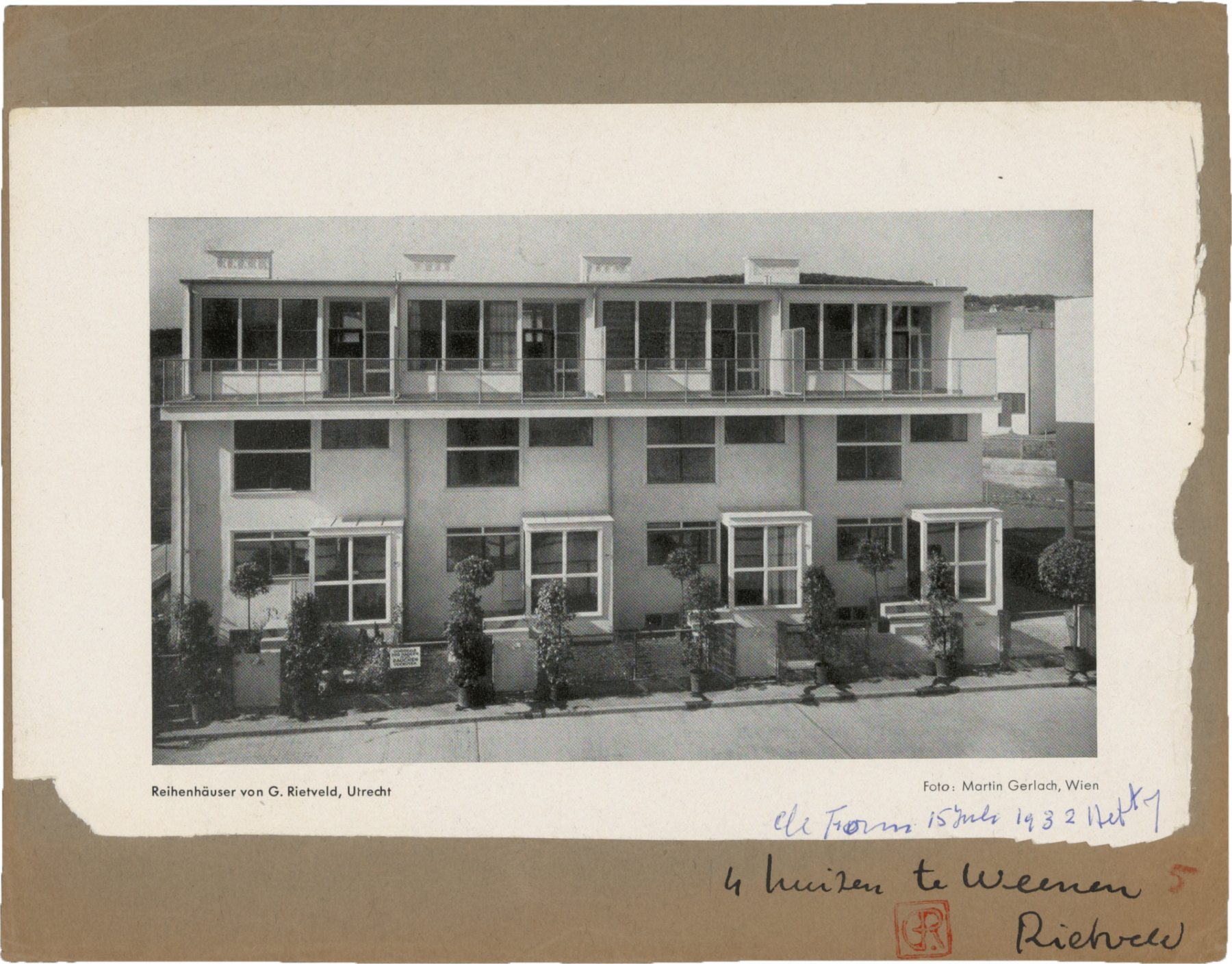

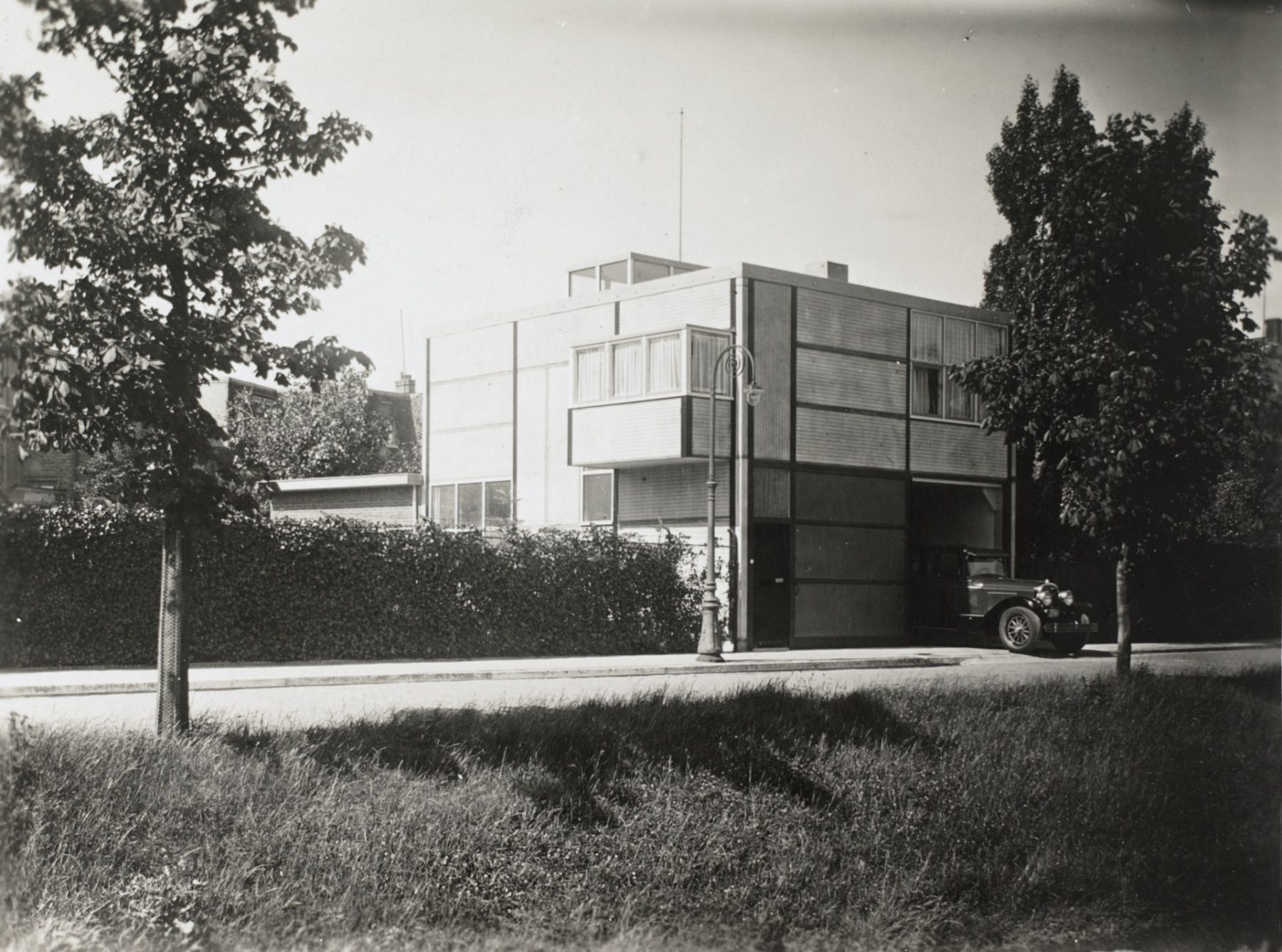

“We had to make all kinds of small things because people in general weren’t ready yet [for his architectural designs]. Because you know, if you want something new whether you do it in politics, painting, sculpture or in architecture, the new that breaks with the old has something un-harmonious. The harmony of the past to which one is accustomed is broken and then there comes a certain opposition and that opposition has to be overcome gradually, not with too much intention. But you can’t let it go. You go on and on and although I do see it now as a line which runs through my whole life’s work, which I did not know at that time of course, I’m sure you notice. I’ve made all kinds of trials and tribulations out of chairs. First I only made small things and I solved all kinds of different problems that I could use very well later on in architecture. Of course you don’t see immediately that it can solve problems for a large building for example. And yet I did that because I had no other opportunity. You actually design a building from a certain construction and from the tasks that are imposed on such a building, all the requirements that are imposed on such a building and you don’t have those if you are going to design a building on your own. Then that study isn’t worth a penny. I’ve always been busy in life, I’ve never made studies besides the assignments. And that’s actually very good. it doesn’t make you fantasise. You stay grounded and as an architect that is of course very necessary. In general I have built mostly villas and country houses. And that was terribly nice of course to get to know the demands of living. Because someone who has some money left over to buy a piece of land and build a house for himself, who pretty much does that for himself, wants to incorporate his whole philosophy of life in it. You learn something from all those people. Although I’m not that demanding at all, from those people I have learned how a person should live and how this can be done well. And I was able to apply that later on also in the social housing and even in the residential houses, but of course that is only possible with very small pieces and chunks, because that is a very economical movement.”