THE PRE-WAR PERIOD (1924-1945)

In 1924 Rietveld handed the furniture workshop over to Gerard van de Groenekan, an employee of the furniture workshop from the very beginning. In 1925 he settled himself as an architect in the Rietveld Schröder house on the Prins Hendriklaan in Utrecht. It was designed in close collaboration with the commissioner Truus Schröder-Schräder.

This house immediately attracted international attention; a design in which he incorporated the ideas of De Stijl with regard to the concepts of function, construction, form and space, as well as those of functionalism.

He expressed about this design: “The house was a study for the new. The main thing was that we no longer worked with the building mass, but with the inner space which could be continued to the outside. No fixed walls either, but sliding walls. This is where all the other work originated from.”

‘The main thing was that we no longer worked with the building mass, but with the inner space which could be continued to the outside.’

Since 2000, the house has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Throughout his life, Rietveld continued to make “small things”, as he called them: furniture, chairs, serving as spatial constructions to solve all kinds of issues, which he could put to good use again in architecture. Initially this was out of necessity, because he received very few commissions. He mentioned about this:

“We had to make all kinds of small things because people in general weren’t ready yet [for his architectural designs]. Because you know, if you want something new whether you do it in politics, painting, sculpture or in architecture, the new that breaks with the old has something un-harmonious. The harmony of the past to which one is accustomed is broken and then there comes a certain opposition and that opposition has to be overcome gradually, not with too much intention. But you can’t let it go. You go on and on and although I do see it now as a line which runs through my whole life’s work, which I did not know at that time of course, I’m sure you notice. I’ve made all kinds of trials and tribulations out of chairs. First I only made small things and I solved all kinds of different problems that I could use very well later on in architecture. Of course you don’t see immediately that it can solve problems for a large building for example. And yet I did that because I had no other opportunity. You actually design a building from a certain construction and from the tasks that are imposed on such a building, all the requirements that are imposed on such a building and you don’t have those if you are going to design a building on your own. Then that study isn’t worth a penny. I’ve always been busy in life, I’ve never made studies besides the assignments. And that’s actually very good. it doesn’t make you fantasise. You stay grounded and as an architect that is of course very necessary. In general I have built mostly villas and country houses. And that was terribly nice of course to get to know the demands of living. Because someone who has some money left over to buy a piece of land and build a house for himself, who pretty much does that for himself, wants to incorporate his whole philosophy of life in it. You learn something from all those people. Although I’m not that demanding at all, from those people I have learned how a person should live and how this can be done well. And I was able to apply that later on also in the social housing and even in the residential houses, but of course that is only possible with very small pieces and chunks, because that is a very economical movement.”

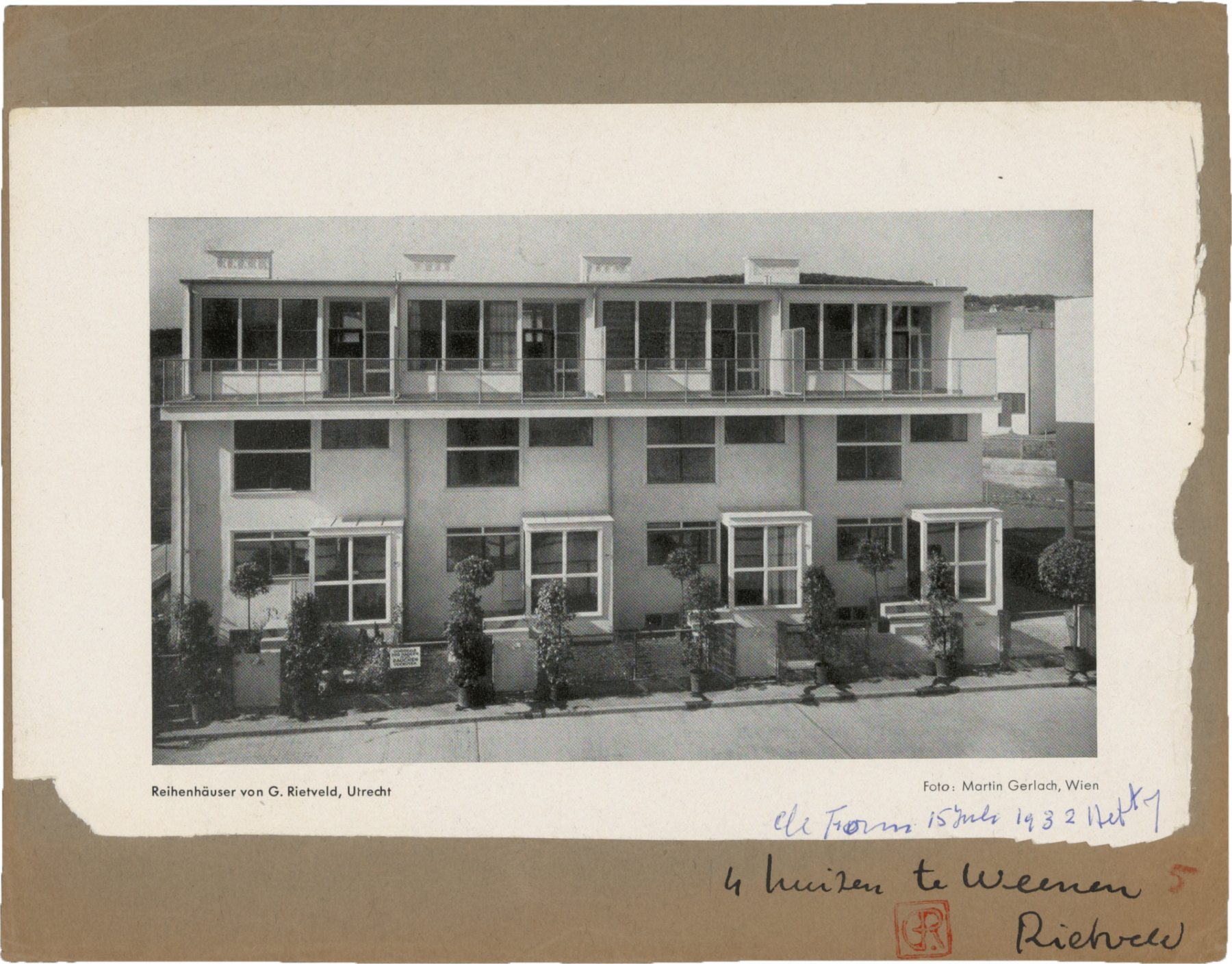

During the first years of his practice as an architect he received few commissions. He built several blocks of houses in Utrecht, such as on the Erasmuslaan (1930 and 1934) and on the Schumannstraat (1931-1932).

Rietveld designed a block of four residential houses in Vienna around 1930, as one of the few foreign architects within the framework of an international Bauausstellung, the Werkbundsiedlung. He received this commission from the architect Josef Frank.

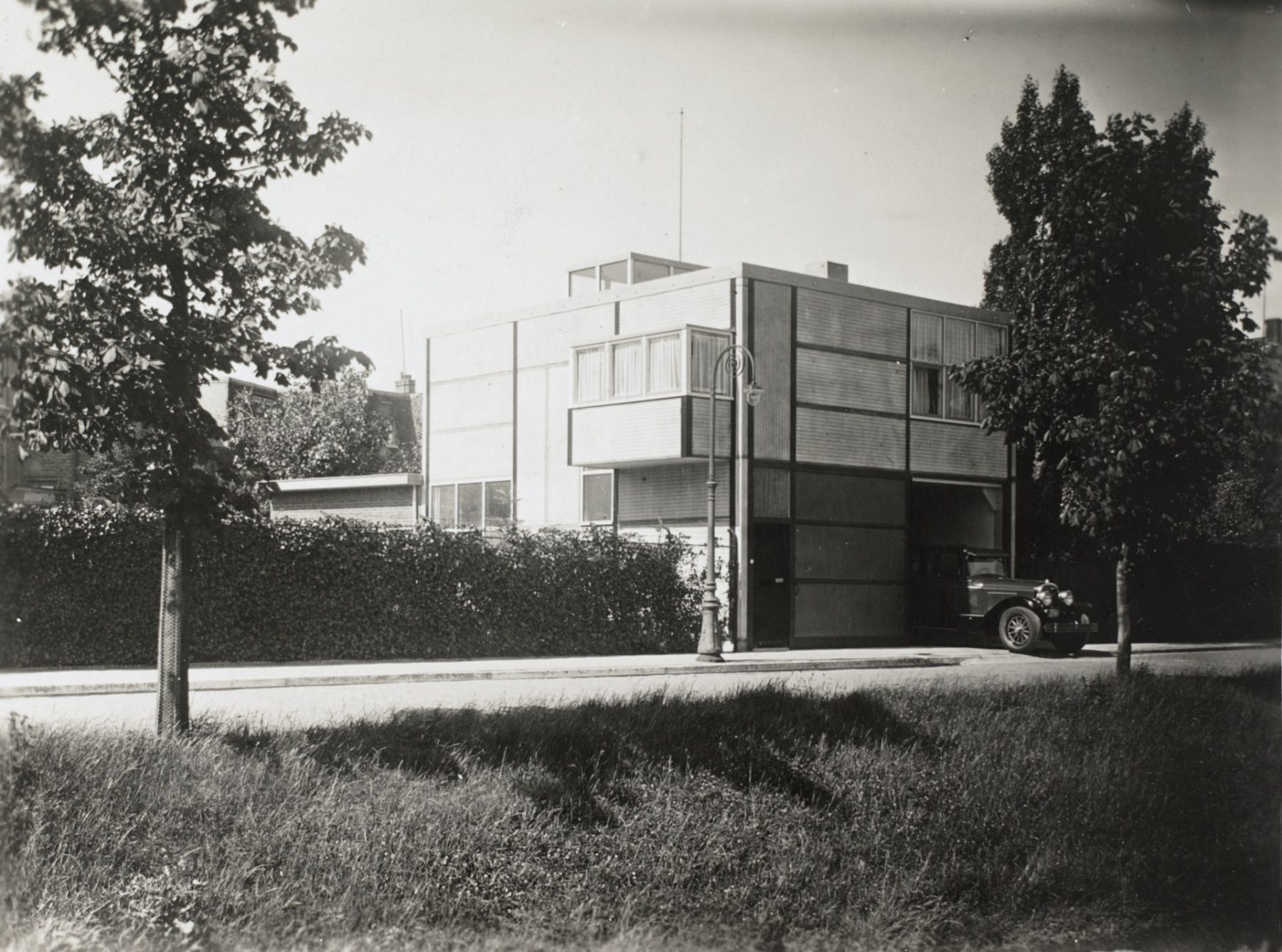

From the end of the twenties Rietveld developed a penchant for popular housing, a home for the masses, preferably industrially produced, to make life cheaper and more pleasant. Experimentation with industrial construction began at the Garage with Driver’s House on the Waldeck Pyrmontkade in Utrecht in 1927.

Rietveld wrote about this design in the avant-garde magazine i10: ‘With this construction an attempt has been made to get one step closer to the factory-built house’. It was his first experiment with an industrial, prefabricated house. A structure of steel profiles filled with factory-produced, glazed concrete facade elements measuring three by one meter. Rietveld himself described it as an ‘experiment for the industrialisation of construction’. It was a revolutionary experiment, especially given the time in which it took place.

This was followed by plans for public housing, also often intended for industrial production. Rietveld wrote in 1929 in the magazine i10: “Corporate architecture must go straight to its goal. We must help simplify life, free it from redundancies. Lighten up the work that remains through consultation, mechanisation and develop the building trade towards a well-organised industrial company with a minimum of passive and coercive work, to provide space to the free mankind…”

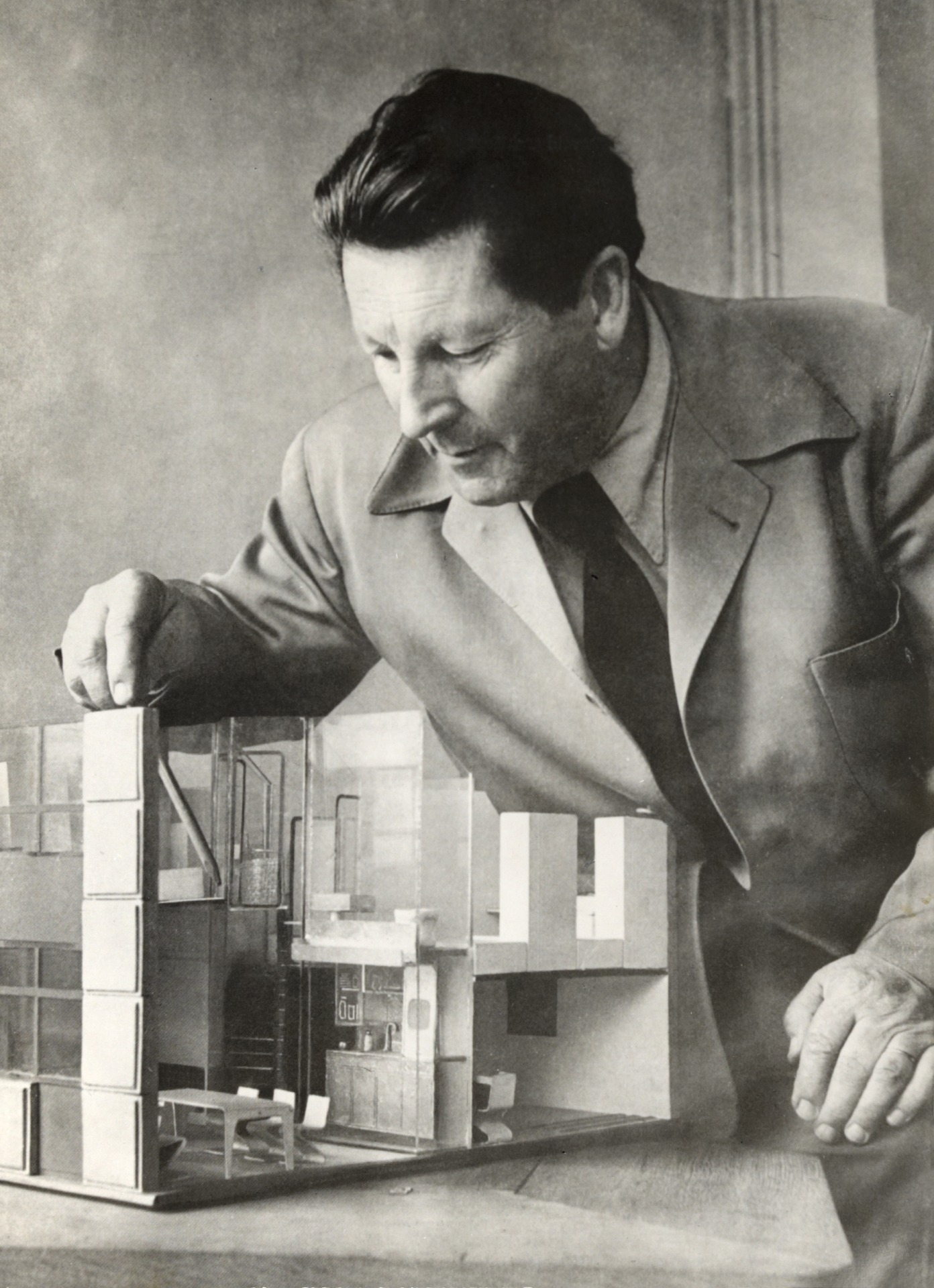

Around 1928 the idea for the Core House was born. In that core the front door, stairwell, toilet, kitchen, bathroom and the water, gas and electricity supplies were included.

The core could be manufactured in a factory and on the building site the rest could be added in staggered floors in a traditional way to make the most efficient use of the usable space. It is a house without corridors, with the stairs as the only traffic space. The space between the front door and the stairs is also a utility room, not a corridor or hallway. In this way, all the space is used efficiently. Unfortunately, Rietveld was unable to realise the core house plans. Only the social housing project in Reeuwijk (1958) shows characteristics of this principle.

In 1928 Rietveld was one of the founders of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) and in 1929, together with Mart Stam, he formed the Dutch delegation to CIAM ‘Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum’ in Frankfurt am Main.

Rietveld was one of the pioneers of Het Nieuwe Bouwen. From an early age he had clear views on architecture: experiencing space, prefabrication to make houses (and also furniture) available to everyone and avoiding the superfluous in order to optimise the use of space.

Rietveld went further and further in removing the boundaries between inside and outside, and he also often made use of new techniques. A subtle play of proportions, the carefully guided incidence of light and the sober finish are characteristic of his houses and buildings.

Important in Rietveld’s work, in addition to the uninterrupted space and light, is the unit of measurement. He noted: “Working well informed and really strict implementation according to units of measurement gives the structure a crystal clarity. If you see a building that has been made strictly according to a unit of measurement, you actually notice nothing about the building, but you experience a clarity that you cannot find anywhere else. This should be not only in length and width, but also in height.”

In the thirties Rietveld built houses for private individuals, especially people from his circle of friends, artists and intellectuals. People who appreciated his designs.

House Székely in Santpoort, built in 1934, shows a refined combination of rectangular and round shapes.

House Hildebrand (1935) in Blaricum has a square based floor plan, with circular and rectangular extensions and a greenhouse against the rear facade. The large glass surfaces are framed in steel and the brick walls are plastered white.

The kitchen and living room are separated from each other by a cupboard wall with pass-through possibility. The kitchen has a small wooden elevator to cool food in the ground. The living room can be divided into two parts with a plywood harmonica wall. This application is also available in the main bedroom. Sliding doors for the toilet and bathroom save space. Such solutions can be seen in many Rietveld houses.

‘If you see a building that has been made strictly according to a unit of measurement … you experience a clarity that you cannot find anywhere else.’

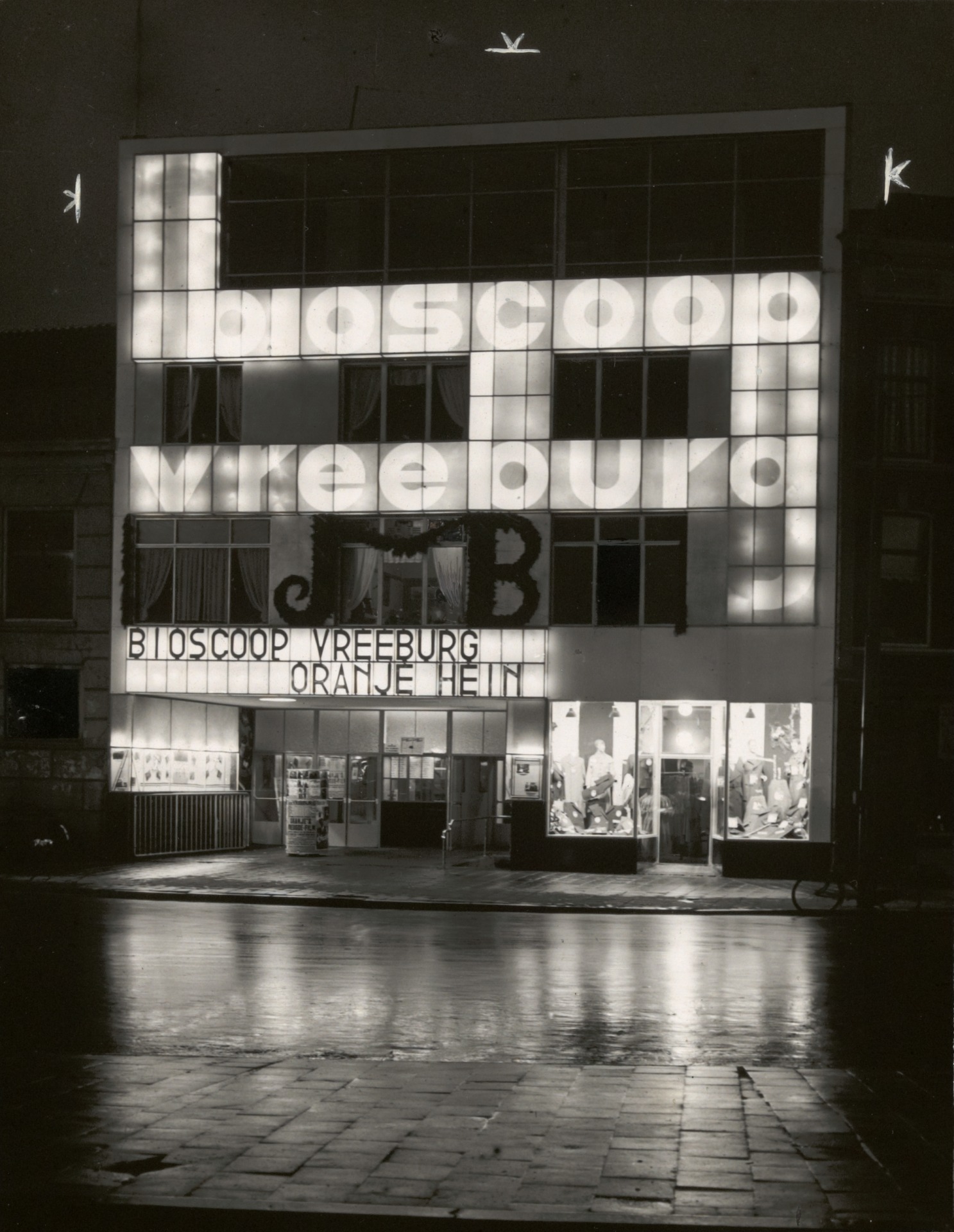

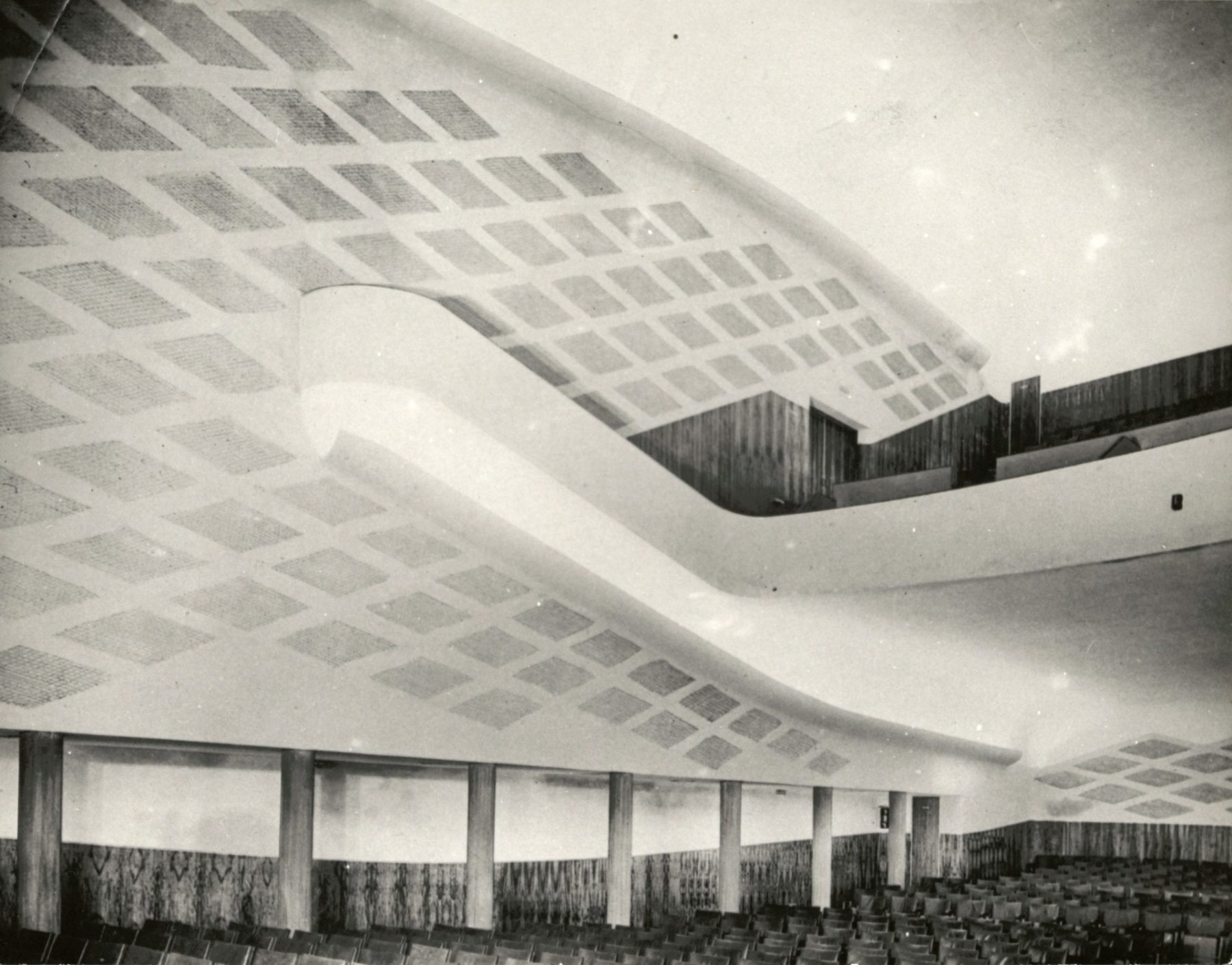

In 1936 Rietveld rebuilt the Cinema Vreeburg in Utrecht. The facade was clad with milk glass behind which light boxes were installed. In the evening the letters ‘Bioscoop Vreeburg’, designed by Rietveld, became visible on the glass.

The interior was special, to improve the acoustics Rietveld had added Genemuider mats in the wet lime of the walls. The chairs were also designed by Rietveld, and executed by Metz & Co, with lilac coloured upholstery.

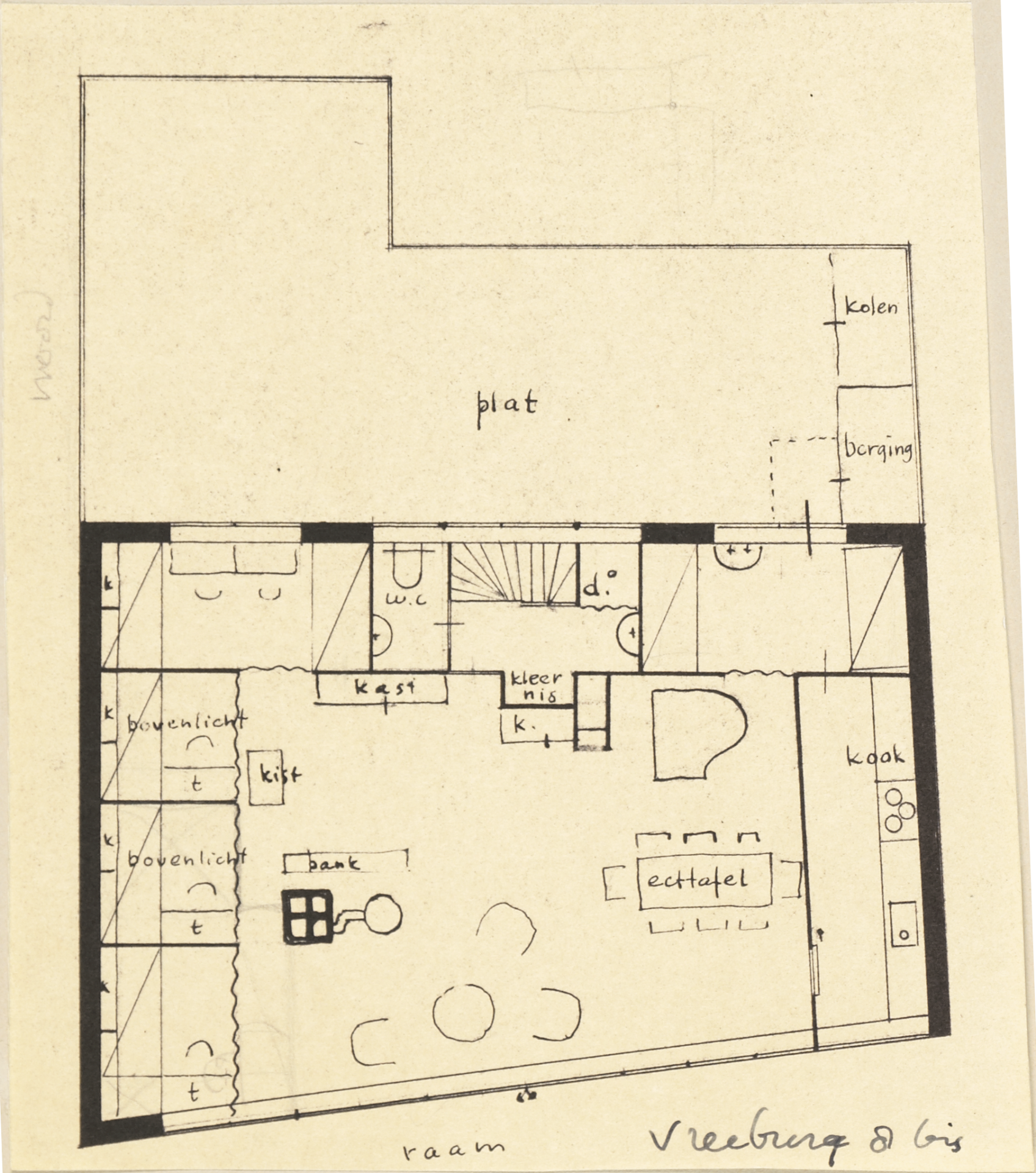

On top of the cinema Rietveld designed an apartment where he intended to live with his family. In his opinion, the interior was the ideal living environment. It consisted of one large space behind an eleven-meter wide glass wall with a view of the Vreeburg. There were alcoves which functioned as bedrooms, with only curtains as a partition to the large living space.